NEW INTERVIEW: [Don’t] Show Your Thing.

ON A LONG CAR RIDE, OTTESSA AND I DISCUSS THE DELICATE NATURE OF CREATIVE FEEDBACK...driving on 10 through a dark desert spring night. Enjoy a window into the weird Socratic ways we chill.

Luke and Ottessa Discuss: GIVING AND TAKING FEEDBACK.

A bit of writerly advice…

Ottessa: So, what’s your advice for writers?

Luke: Don’t ask for feedback on projects you’re still in the middle of. Successful, intelligent people are stingy with their thoughts and time. Dumb, unsuccessful people are incredibly generous — and will give you all their best thinking, which will be stupid and wrong. So just don’t ask.

Ottessa: Do you think that’s why we had so much conflict whenever you’d ask you for feedback?

Luke: Yeah. Because you’re incredibly smart and successful — and you’re stingy with your time and energy. And I’m soooooo stupid! Very funny.

Ottessa: Yeah, and yet… you kept asking.

Luke: Yeah. And what happened?

Ottessa: We fought.

Luke: Exactly. That’s what I’m saying. You can’t really go to anyone.

Ottessa: Oh my God. Is this an apology?

Luke: It wasn’t… I didn’t plan for it to be, but—

Ottessa: Do you remember what happened in Hawaii?

Luke: Okay, it can be an apology. But yeah, I think the point stands. I mean, I’m sure there are sweet spots — people who are actually smart and can give you something helpful. But maybe the advice is: just talk about the project with intelligent people. Don’t ask them to read it. When I’ve shown people scripts, they say things like, “I don’t like this,” or, “There’s no character I care about.” They just don’t see the potential. And I can’t convey it to them. So their responses are feeble-minded and kind of pathetic.

Ottessa: Don’t you think that just means you’re sharing too early? If people can’t see it yet, maybe it’s because it’s not there yet.

Luke: Not always. It depends. I’ve shared some things with different people and gotten a range of responses. Other times, I’ve shared something with one person and just thought, “Oh… you’re not smart enough.” And sometimes I feel like I’m the person who isn’t seeming smart enough. For example, I met with someone very famous recently, and they gave me a script that was… well, kind of bad.

Ottessa: Wait, we’re recording this.

Luke: Yeah, you’re right.

Ottessa: Okay, so say it wasn’t so bad. Ha.

“I find it most helpful to ask other writers about what they're going through in the process of their own novel writing.”

Luke: Actually, it wasn’t. My point is: They can see what it’s going to be. They know more about it than what’s on the page. When I met with them, I thought, “Oh — I have faith in this person.” They’re good at what they do. And the way they took my feedback, it felt like they already knew no one else really gets it like they do. Because they’re listening for what’s useful to them and they know more than they’re showing.

Ottessa: Yeah, okay. That’s fine.

Luke: I think maybe it's more useful to just talk through what you're doing on a project with someone who's intelligent. Then it's not so much of an ask. Because when you would be reading my work, you'd be like, “I don't like this sentence. I don't like the way this is.” You know what I mean? You get hung up on all the things that it's not quite yet.

Ottessa: Yeah, because you're presenting something that hasn't really been baked. I could show you the recipe for some cookies, but you wouldn't know if it was going to taste good until I made them and presented them to you. But I find it most helpful to ask other writers about what they're going through in the process of their own novel writing. Because if you're looking for a... what is that expression? If you're looking for a thing, you'll find a thing.

Luke: There are a lot of aphorisms, like, "to a hammer, everything is a nail."

Ottessa: Oh yeah, like if you pick up a hammer, you'll find a nail.

Luke: That's not exactly what I'm saying. I'm not sure that's the expression.

Ottessa: Well, I'm saying it as a new expression and I am also not saying it’s perfect yet.

Luke: Right. Because if you pick up a hammer at an airport, you're probably not going to find a nail.

“If I ask someone what they're doing with their novel, and I actually inquire, my own narcissistic writer mind will glean from it something useful for my own experience.”

Ottessa: Can I just finish what I want to say?

Luke: Yeah.

Ottessa: Before you completely derail this with a stupid joke. God. When I was writing a lot of short stories, I had this theory that I can't make a wrong move. So whatever you do is pushing you toward where you're supposed to go. And I think the same kind of thinking holds true for when I'm in a bind or a moment of indecision with a novel. If I ask someone what they're doing with their novel, and I actually inquire, my own narcissistic writer mind will glean from it something useful for my own experience. But I also want to say that when I was writing Eileen, I had this very strong theory for decades that you should never, ever talk about what you're working on because it lets out all the pressure and makes it seem stupid.

Luke: I think you'll then see it through the eyes of someone who can't understand it. And they can't understand it because it doesn't exist yet. I'm starting to get over that superstition. But that was one of Rupert Dick’s commandments.

Ottessa: I certainly didn’t learn that from Rupert Dick’s.

Luke: What about from Peter Markus?

Ottessa: Is everything that you know because someone taught it to you?

Luke: No, but that’s a connection we share, someone who espoused that belief. So I thought perhaps you'd gotten it from him.

Ottessa: I mean, I don’t think it’s very uncommon. That’s why people are like, can you talk about it?

Luke: Yeah, you're right. I think a lot of people look for feedback and ask someone to read something. And have bad experiences and so it becomes a thing… a superstition. Maybe most superstitions come from some experience that makes them evolutionarily useful. Because they're usually asking for permission. Like, is this good enough? Instead of, what do I need to see that I'm not seeing? And I think a lot of people get feedback from a place of judging it as worthy or not worthy. Instead of like, what am I missing?

Ottessa: So what do you do when a friend shows you something they're working on and it is just partially baked and you don't feel confident about where it's going? How much effort do you put into your feedback? And is it fair to give inventive ideas to people?

Luke: I feel like that's bad juju. This is still something I'm working on, primarily in the script world. Because oftentimes I'm getting things and I'm wondering if there's opportunity for collaboration where I could produce or I could write or be involved in some way. Sometimes it's brought to me directly with that question. And sometimes we’re feeling whether or not that's an opportunity. So I want to give thoughts and have a take on it. That would indicate that there's some ability for us to inhabit that space together and make it better.

Ottessa: Okay. So sort of like dating.

Luke: Right.

Ottessa: Yeah. Good one. No.

“I don’t show someone a piece of my writing to hear about how everybody can understand it. What do you mean everybody can understand it?”

Luke: I think it’s a sign of a weakness when people are strongly negative about scripts or anything, really. So if something’s really unsalvageably bad, in my opinion, or not working and I can't figure out how to make it work, I tend to just be more positive. And if there's something there that needs work, I still lead with positivity and generosity. It’s your question as to whether or not I'm prescriptive or inventive — I'm inventive. I'll take something apart and try to put it together again in a different way or ask questions about it. I guess that's it. I like to ask questions about it and figure out what it's doing and why it's relevant to others, why it's immediately appealing to others. What's universal about it? What is it dealing with in terms of the zeitgeist or theory or shared humanity or inhumanity?

Ottessa: Oh, I would hate to hear that. I don’t show someone a piece of my writing to hear about how everybody can understand it. What do you mean everybody can understand it? You're saying that it's in the zeitgeist, like tapping into what everybody else is doing.

Luke: No, I just mean, why is this interesting to more than a few people? For instance, why is My Year of Rest and Relaxation interesting? It's interesting because it's about grief. It's about processing grief. It's about wanting to hibernate. It's about wanting to heal or not heal, not deal with what's too much.

Ottessa: You always do this…

Luke: This makes sense.

Ottessa: But that's not feedback. That's just kind of like a review.

Luke: Right, but that's because it's a finished project. But if you brought it to me and it was doing some of that and some of something else and some of something else and it wasn't clear yet, I might zero in on that as the thing that's really powerful.

Ottessa: How do you know that that's what you would zero in on? It's easy to say that in retrospect, but if you saw an early draft of it, you might zero in on something completely different.

Luke: But I'm saying my method is to look at that first, what's interesting and compelling. What's the style? What's the tone and all that? But most importantly, well, what is it about? What is this essentially dealing with? How is this fucking everyone up on Earth all the time?

Ottessa: Yeah. Okay. And so what?

Luke: So that's what I look for when I'm reading something. So I think that I am psychically feeling for what’s real inside the writer and their work. Of course. Like anyone.

Ottessa: Are you talking about movies?

Luke: No, I’m talking about everything. Books, movies, documentaries, anything that's a story.

Ottessa: I feel like when I write a novel and when I read a novel, the last thing I want to think about is how I could summarize what it’s about.

Luke: I’m not talking about summarizing. So what is the first thing you want?

Ottessa: Well, that’s what you’re asking: What’s the core question that this story is asking?

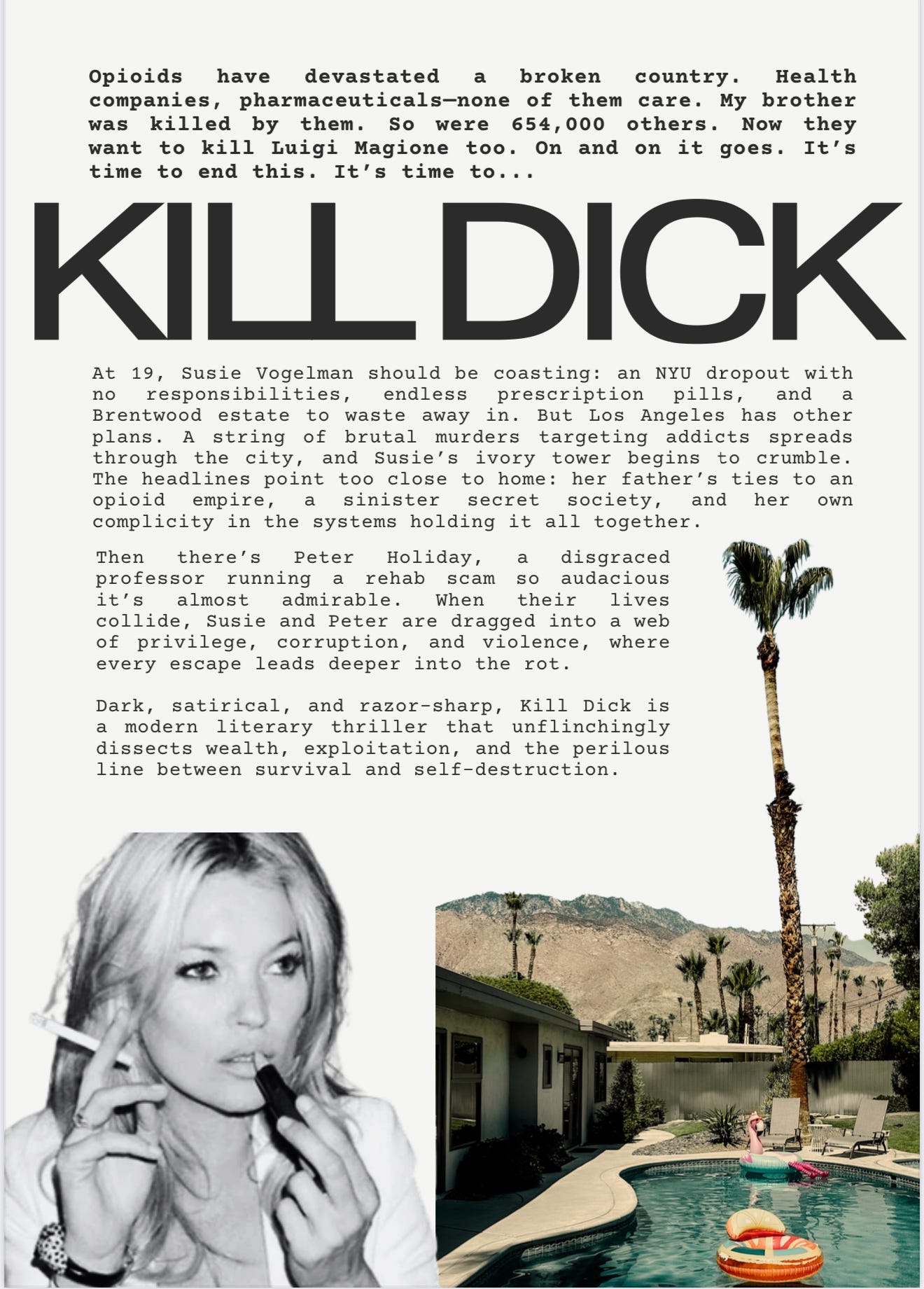

“In my new novel, KILL DICK, there are things that usefully and purposefully aren’t clear…The experience is in the words on the page, and people can think whatever they want.”

Luke: Okay, let’s put it a different way. What is the thing that you're wanting to spend years doing in a novel or a film? Like, why is this personal to you in terms of how your soul is going to grow by looking at that thing? What are you being asked to engage with? What are you going to go inside to bring out?

Ottessa: So, that's a novelist question, not a screenwriter question.

Luke: No, it's a screenwriter question too, don't you think? I mean, sure, you have to be a really good writer to get to that level with screenwriting. To write a great action movie. You’re probably not starting there.

Ottessa: When you read Taxi Driver, for example, you're like, this person understands film, how a film is shot and edited and put together, the rhythm of it, and the music. And he has written this psychic pre-interpretation of it, you know? And I feel like that's so rare.

Luke: Because he's really making a film, he's not just writing a script. He’s working with the director. Which is so key. Any movie I can write with a director, I’m so much fucking happier.

Ottessa: It's really hard to see the film if you're just reading the script unless there's a real film under it.

Luke: Yeah, it's a confounding form. You can read a really well-written script. Like Tarantino says, a script should be a form you enjoy unto itself. I read a script recently with someone, and we wrote it, and I’m like, this is really, very well-written, but I’m not sure it’s a good film yet. It could just be powerful in terms of language and dialogue, but it may not work as a film yet. Directors are so fucking brilliant. Actors. Everyone. If you can work with anyone else, that’s so nice.

Ottessa: Uh huh.

Luke: With Taxi Driver, do you... I was talking to that guy I told you about who wrote about Luigi Mangione for the New York Times Magazine. He was talking about Taxi Driver and how professions and jobs are always used by Paul Schrader. He picks what the person does for a living to be emblematic and key to the character’s journey. Like being a taxi driver is about loneliness. You're always with people, but only for short periods. They don’t engage with you.

Ottessa: Exactly. The opening of that movie is incredible. I would think Schrader would have known that’s what he’s working on—that the guy is lonely, surrounded by people, yet completely isolated. He's probably a war vet, wearing that jacket. But when you're writing a novel, there isn't any 'probably.' You’re writing the actual thing that someone will experience.

Luke: I don’t understand what you mean by that. In my new novel, KILL DICK, there are things that usefully and purposefully aren’t clear. You finish it, and I hope you wonder—what was this or that? The experience is in the words on the page, and people can think whatever they want. But there’s a mystery because I want it to be a mystery for the meaning of the work. It’s the opposite of a film, in many ways, because with a film you have to bring it together. This book is the cover-up and the story itself is about the fake. The hyperreal. I can’t explain it right now in the purview of this subject. But the experience of watching a movie isn’t the reading of the script.

Ottessa: Right. One is the finished form, and the other is a step toward the finished form.

Luke: So, what does that have to do with thinking about things in terms of central issues or themes?

Ottessa: Suppose Schrader asks, what’s the major thing happening here? He’s asking himself, what’s this about? But that kind of inquiry isn’t helpful in writing screenplays...

Luke: Why not? What about your current project with Alice? You’re not engaging with these questions? You said on the phone from Italy, you asked—what do you have when you lose your beauty and intellect, and all you have is your talent?

Ottessa: That’s a central theme.

Luke: You’re asking what happens when you lose parts of yourself that were your identity, and how you go on.

Ottessa: Yeah, that’s a central theme, and I’m writing a movie.

Luke: What’s your current novel about?

Ottessa: My novel is still discovering what it is. I’m not arguing that I’m right and you’re wrong. I’m talking about how I feel about the two different forms. With a movie, you have to know ahead of time. With a novel, you’re figuring it out for a very long time until it’s a complete first draft. With a screenplay, you can’t just write a movie and figure it out later.

Luke: You’re right. But when it comes to feedback, I would approach reading someone’s script or discussing a film with the same basic question: What is this about that would be resonate with others? What’s universal? What is the soul trying to learn or explore in this imaginary experience?

Ottessa: Don’t you think those are two different questions? What is universal, and then what is personal to you?

Luke: I think it’s just a coincidence. Both have to happen at once. Film is different. It costs money to make, while writing is just the writing. A book takes more time, but it's expensive in terms of people's attention span. But all of them need that perfect coincidence. Or you have to stay with them and work for sooooo many years until it occurs. You have to will it.

“I see feedback as trying to get to that spiritual thing—the thing that’s grander than just the basics.”

Ottessa: Well, it’s easier to watch a movie than it is to read a book. It's like asking someone to look at a painting versus asking them to read your novel.

Luke: I just think it’s kind of like the Kabbalah or Tree of Life—if you tap into something really important to you, you’ll articulate it well, and it will be universal. Art works because we’re all connected by a spiritual union.

Ottessa: Yeah, well, that’s easy to say.

Luke: Yeah, it’s hard to do, but that’s what we’re trying to do, right? Story works when it’s done right.

Ottessa: I see feedback as trying to get to that spiritual thing—the thing that’s grander than just the basics.

Luke: I’m in a completely different point of view. When I give feedback, asking what their soul wants to learn is patronizing. I can’t help but rewrite things as I read them. I’ll offer suggestions to fill gaps I see, but feedback for novelists is kind of pointless. By the time the book is ready to get feedback, it’s formed. It just needs an editor, a great editor.

Ottessa: I agree. You can’t help someone unless they’re at a point where everything’s formed, where it’s a finished thing. Only then does it feel like the thing it’s meant to be. If it hasn’t found its life yet, no one can help. When something isn’t ready, I just don’t know what to say about it. I need to see something formed.

Luke: That’s exactly what you said to me when you read the first draft of this book eight years ago. It was devastating.

Ottessa: I said that out of respect, though.

Luke: But you were right. Sometimes you just have to say, “I don’t know what to say about this.” And that’s what I need to learn, too. You can’t talk about something that isn’t formed. There’s a point when a novel is ready for feedback. It’s way later, like showing your cut of a film. But I think you can always talk about the idea. A script is different because it’s meant to be collaborative unless it’s an auteur-writer-director. Then just ask to see the first cut.

Ottessa: So, is this stressing you out since you’re about to edit your novel?

Luke: No, I feel good. I feel really good.

Ottessa: You’re eating your fingers a lot. What do they taste like?

Luke: Salt. And kind of like… I’ll tell you later.

Honest and insightful stuff. The Paris Review wishes it had interviews like this.

a) what happened in hawaii though?

b) i completely agree about talking about a novel/project when it's unbaked rather than showing to someone - the most useful thing i found for propelling/shaping my one (1) novel was to go for a long walk with my husband and make him listen to me talking through it all for 1-2 hours. i would honestly have revelations (the walk element is crucial because he can safely zone out without me realising)